Congo (Brazzaville)

The plot:

Large scale plans for tar sands bitumen extraction have been proposed for a few years, whereas multiple community activists from within the Congo have demanded proper consultations and environmental impact assessments that have not yet been undertaken in a transparent manner. If plans for extraction went ahead, tar sands developments would have a foothold within continental Africa.

The details:

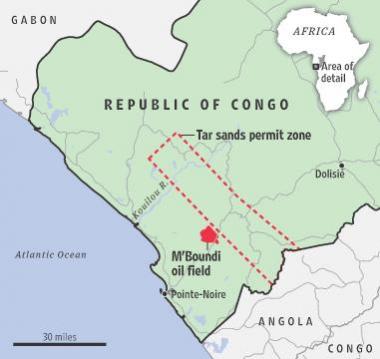

There are two main tar sands bitumen deposits, both in the Congo Basin.

Combined total of deposits (in an area slightly less than 1800 km2) estimated between 500 million and 2.5 billion bbl recoverable.

In-situ likely given the depth of the deposit; original permits granted were from mining authority within the government. All plans are for synthetic oil production, though no technological means have been made public. Permit has been re-signed.

ENI, partially state owned by Italy, has not made preliminary or long-term daily production totals public. Initial plant projected to extract 150 million barrels over the life of the project.

The tropical forest cover of the approximately 1800 square km permit area is roughly 70%. The Republic of Congo is vital to forest cover that acts as a buffer to the worst impacts of climate change. Resource profits from oil and gas are often taken without benefit to the local population, a population still often living in extreme poverty. Inadequate means, to say the least, of consultation among the populations have been cited as a specific problem for ENI's contract. Further exacerbating problems of environmental impact has been ENI not releasing to the public sphere their plans for extraction methods and technology.

Alongside Madagascar, many other countries in Africa can see tar sands getting a test run in Congo-Brazzaville. ENI (along with companies like TOTAL) are determining what requirements, regulatory regimes and revenue breakdowns are being demanded or required of international energy companies when it comes to extreme extraction in Africa. The impacts on global climate change (as a result of both extraction itself, as well as deforestation and carbon emissions stemming from development) and local indigenous control in the face of corporate malfeasance in Congo is symptomatic of energy interests throughout the region.